Nyani Ngabu

Platinum Member

- May 15, 2006

- 92,236

- 113,610

- Thread starter

- #321

UMENENA, UMENENAUkiwa kiongozi mwenye msimamo hata watu wanaotofautiana nawe watakuheshimu. Ukiwa mtu usiye na msimamo hata wanaokudharau watajifanya wana kuheshimu.

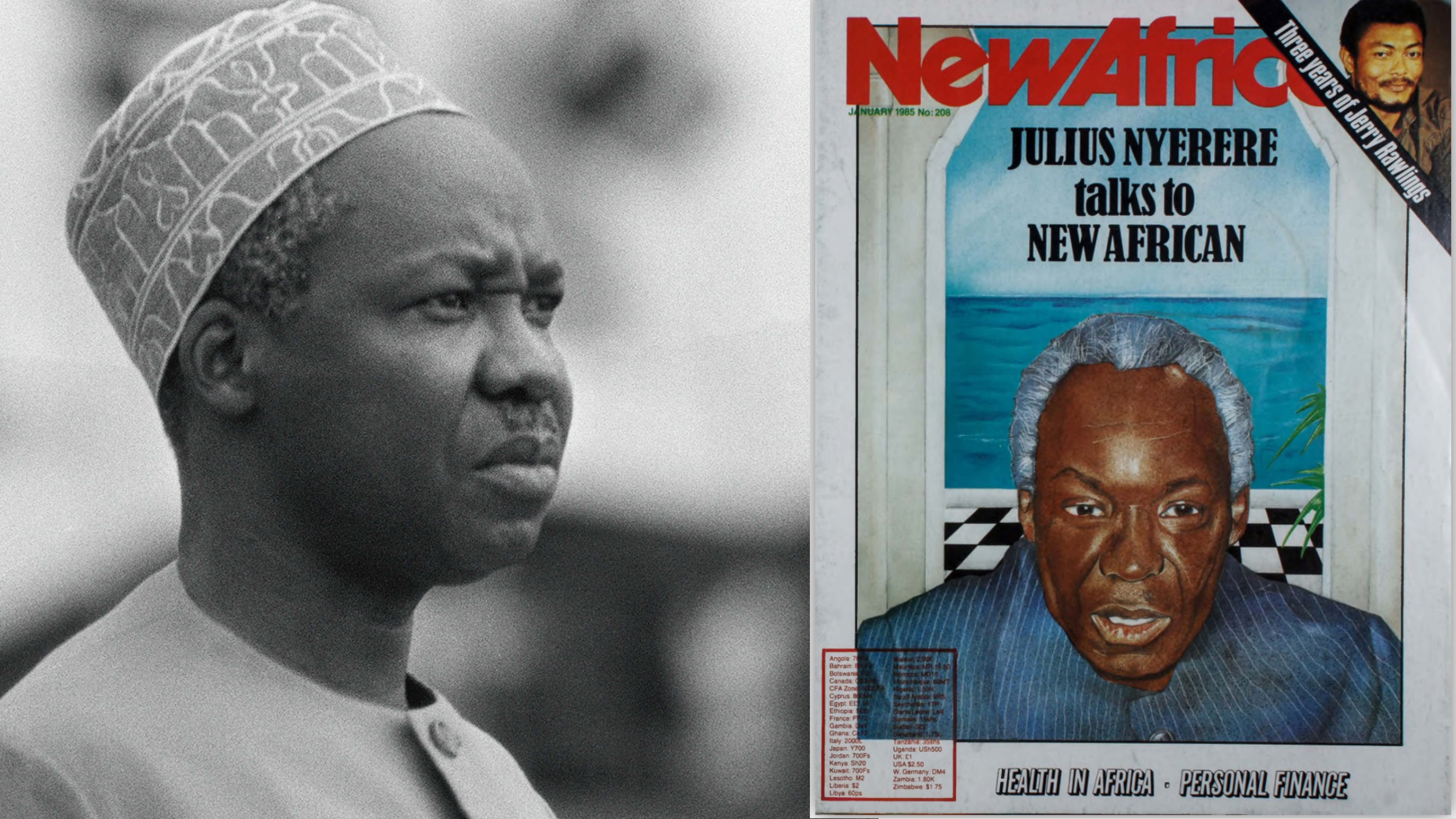

A glowing tribute of Mwalimu by PLO Lumumba.

newafricanmagazine.com

newafricanmagazine.com