donniebrasco

JF-Expert Member

- Aug 8, 2013

- 887

- 770

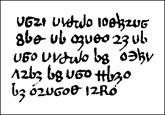

Wenyewe CIA wanadai kuwa walishapata majibu ya sehemu tatu bado sehemu ya nne ili kiujumla ndio wajue maana ya fumbo hili.

Fumbo hili lipo makao makuu ya CIA Langley, Virginia kama linavyoonekana hapo juu.