Kurzweil

JF-Expert Member

- May 25, 2011

- 6,622

- 8,397

An Explainer for When the Internet Goes Down: What, Who, and Why?

Isabel Linzer, Research Associate

Since 2017, authorities in 19 African countries have temporarily blocked social media or restricted internet service. Last month’s shutdowns in Ethiopiaand Mauritania were just the latest in a long pattern.

Often lost in the wave of incidents, however, is a clear examination of the distinctions between each case. What are the different mechanisms being used in different contexts? What are the various motivations behind them? What is actually going on and why does it matter?

What do all these terms mean?

There are various types of internet restrictions, though the terminology for these different types is sometimes used interchangeably, making it hard to discern what is really happening. Here is a breakdown of the main categories:

Shutdowns/Blackouts

During a shutdown, there is little to no network connectivity. All systems of communication that rely on the internet – social media platforms, internet-based voice and messaging applications, ordinary websites – are rendered inaccessible.

Shutdowns can be nationwide. Following an alleged coup attempt in Ethiopia on 22 June, for example, an internet blackout was imposed on up to 98% of the country. They can also be more targeted. Cameroon’s Anglophone regions suffered a 93-day network shutdown in 2017, while Gabon’s shutdown earlier this year did not affect the entire country either.

Though other means of communication, such as regular phone connections, are not directly affected by a network shutdown, there are currently no tools that allow people in the country to circumvent these restrictions.

Throttling

Short of turning off the internet entirely, governments can slow down the network artificially in a strategy known as throttling. Because similar connectivity problems can also be caused by poor infrastructure or technical errors, throttling can be harder to identify than a shutdown. Some governments, however, make no effort to hide their restrictions.

In August 2017, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) engaged in throttling amid protests against then President Joseph Kabila’s refusal to step down. The internet was slowed down to the point that images could not be shared on social media.

The specific order from the telecommunications regulator to the internet service providers (ISPs) said: “In order to prevent the exchange of abusive images via social media by your subscribers, I ask you to…take technical measures to restrict to a minimum the capacity to transmit images.”

In addition to slowing the entire network connection, throttling can also be used to target specific apps, IP addresses or websites. In cases of selective slow downs, individuals may be able to use virtual private networks (VPNs) to circumvent the restrictions, but not if the entire network is affected. Users in countries at risk of connectivity disruptions should consider downloading VPNs preemptively because doing so once networks and platforms are disrupted can be challenging. (This guide from Quartz is a good place to start.)

Blocking

Unlike shutdowns and throttling, which affect overall connectivity, blocking specifically targets access to certain platforms or content. Blocking entire social media platforms or popular messaging applications can have much the same effect as network shutdowns: the ability to communicate is severely limited and access to information is restricted. In many countries, certain social media companies serve as the main portal to the internet. They are a communication tool, the primary source of news, and an entertainment hub rolled into one.

The duration of blocking varies hugely. Chad’s block on social media and messaging platforms – such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Viber – lasted 16 months before it was lifted this month. Liberia’s restriction off Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and WhatsApp on 7 June lasted less than a day.

Uganda offers a unique example of the complex nature of blocking. When a new social media tax went into effect on 1 July, 2018, more than 50 platforms were blocked, but only for users who had not yet paid the tax. In order to enforce the blocking, and with it the tax, the government also blocked many VPNs.

Users looking to get around blocking can use VPNs and can learn from Uganda by preemptively downloading multiple VPNs in case the one or more are blocked or fail.

Who is doing what?

Identifying the process by which internet restrictions are put in place can reveal whether the government, the internet service provider, or some other actor was responsible. Complicating matters, however, is that governments often initially deny any involvement.

Orders to ISPs

For a government to implement restrictions on network connectivity or social media, it usually requires the compliance of ISPs.

Internet providers take a financial hit when the population can’t use their services so why do they comply? Often the answer is fear of retribution or legal consequences, including the loss of their operating licenses or even prosecution of their executives.

During the network shutdown during the 2018 election in the DRC, internet provider Global texted customers explaining that the government ordered a network shutdown. Vodacom told reporters the same thing.

Service providers in the DRC have been similarly transparent in the face of shutdown requests in the past, citingtheir legal obligation to comply.

Government-controlled infrastructure

In certain cases, there is no need for the government to go through private-sector middlemen when it wants to restrict connectivity. This is the case in Ethiopia, where the government has a monopoly on the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. EthioTelecom, the sole provider in the country, is state-owned. This type of centralisation enables the government to restrict internet access at will

What’s the point?

Governments justify internet freedom violations in a number of ways, but there are a few common triggers.

Protests

Already in 2019, protests have prompted restrictions in a number of countries including Sudan, Liberia, and Zimbabwe. Social media are powerful organising tools so some governments see restrictions on them as a way to tamp down popular mobilisation.

Limiting communication can also prevent the spread of news about the state’s human rights violations. This reasoning was cited as a concern in Zimbabwe and Sudan.

Unfavourable news

When the Chadian government blocked social media beginning on 28 March, 2018, it was not in response to a particular external catalyst. Instead, the authorities were reacting to a constitutional reform proposal that would allow the long-time president to serve additional terms in office. The blocking was apparently an attempt to prevent protests or other backlash against the plan, which was likely to be unpopular.

Exams

Shutting down the internet during exams may seem comparatively innocuous, but it is a disproportionate response to the risk of cheating and sets a precedent for abuse in the future. Algeria has made a habit of exam-related shutdowns as has Ethiopia, most recently in June.

Elections

Elections are a flashpoint for other internet freedom violations, so it is no surprise that some elections have been accompanied by social media blocks or network shutdowns in the last few years. This year began with the internet being disconnected in the DRC following a disputed presidential election in late December. A few months later, service was shut down on election day in Benin. The latter case was seen as more of a surprise, as Benin has generally been considered one of the more reliable democracies in Africa.

Why this matters

A 2015 UN joint declaration asserted that network shutdowns “can never be justified under human rights law.”

No matter the type of restriction, how it was enacted, or what reasoning is provided, wholesale internet disruptions and social media blocking are never worth the problems they cause.

Even supposed national security concerns and the fight against “fake news” do not outweigh the very real consequences of cutting off access to information for millions of people.

Network and social media restrictions limit freedom of the press and freedom of speech, and can entail enormous economic costs. In the case of the DRC, UN special rapporteur for freedom of expression David Kaye echoed the 2015 UN declaration, calling the country’s shutdown “a clear violation of international law.”

He also pointed out that the shutdown undermined electoral integrity and damaged people’s access to basic services. Perhaps most importantly, such violations deprive individuals of the ability to communicate with friends and family, often at a time when public safety may be compromised.

If they are concerned about maintaining order at sensitive moments, governments operating in good faith would do better to increase transparency, encourage the dissemination of accurate information, actively debunk falsehoods, and directly address the grievances that might lead to criticism or unrest in the first place.

This article was first published by African Arguments July 24, 2019.

Analyses and recommendations offered by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of Freedom House.

Isabel Linzer, Research Associate

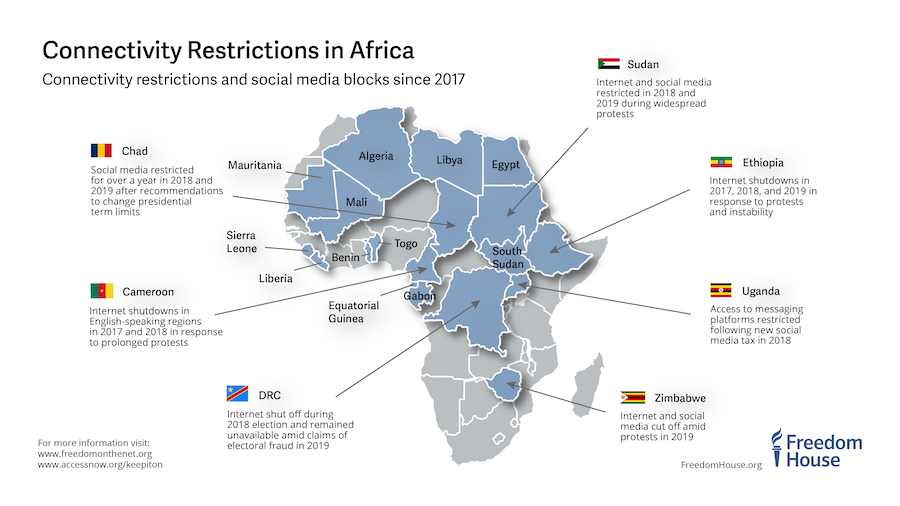

What’s the difference between a block and a blackout? Who’s responsible? What can be done?Map highlighting connectivity restrictions and social media blocks in Africa since 2017

Since 2017, authorities in 19 African countries have temporarily blocked social media or restricted internet service. Last month’s shutdowns in Ethiopiaand Mauritania were just the latest in a long pattern.

Often lost in the wave of incidents, however, is a clear examination of the distinctions between each case. What are the different mechanisms being used in different contexts? What are the various motivations behind them? What is actually going on and why does it matter?

What do all these terms mean?

There are various types of internet restrictions, though the terminology for these different types is sometimes used interchangeably, making it hard to discern what is really happening. Here is a breakdown of the main categories:

Shutdowns/Blackouts

During a shutdown, there is little to no network connectivity. All systems of communication that rely on the internet – social media platforms, internet-based voice and messaging applications, ordinary websites – are rendered inaccessible.

Shutdowns can be nationwide. Following an alleged coup attempt in Ethiopia on 22 June, for example, an internet blackout was imposed on up to 98% of the country. They can also be more targeted. Cameroon’s Anglophone regions suffered a 93-day network shutdown in 2017, while Gabon’s shutdown earlier this year did not affect the entire country either.

Though other means of communication, such as regular phone connections, are not directly affected by a network shutdown, there are currently no tools that allow people in the country to circumvent these restrictions.

Throttling

Short of turning off the internet entirely, governments can slow down the network artificially in a strategy known as throttling. Because similar connectivity problems can also be caused by poor infrastructure or technical errors, throttling can be harder to identify than a shutdown. Some governments, however, make no effort to hide their restrictions.

In August 2017, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) engaged in throttling amid protests against then President Joseph Kabila’s refusal to step down. The internet was slowed down to the point that images could not be shared on social media.

The specific order from the telecommunications regulator to the internet service providers (ISPs) said: “In order to prevent the exchange of abusive images via social media by your subscribers, I ask you to…take technical measures to restrict to a minimum the capacity to transmit images.”

In addition to slowing the entire network connection, throttling can also be used to target specific apps, IP addresses or websites. In cases of selective slow downs, individuals may be able to use virtual private networks (VPNs) to circumvent the restrictions, but not if the entire network is affected. Users in countries at risk of connectivity disruptions should consider downloading VPNs preemptively because doing so once networks and platforms are disrupted can be challenging. (This guide from Quartz is a good place to start.)

Blocking

Unlike shutdowns and throttling, which affect overall connectivity, blocking specifically targets access to certain platforms or content. Blocking entire social media platforms or popular messaging applications can have much the same effect as network shutdowns: the ability to communicate is severely limited and access to information is restricted. In many countries, certain social media companies serve as the main portal to the internet. They are a communication tool, the primary source of news, and an entertainment hub rolled into one.

The duration of blocking varies hugely. Chad’s block on social media and messaging platforms – such as Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Viber – lasted 16 months before it was lifted this month. Liberia’s restriction off Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, and WhatsApp on 7 June lasted less than a day.

Uganda offers a unique example of the complex nature of blocking. When a new social media tax went into effect on 1 July, 2018, more than 50 platforms were blocked, but only for users who had not yet paid the tax. In order to enforce the blocking, and with it the tax, the government also blocked many VPNs.

Users looking to get around blocking can use VPNs and can learn from Uganda by preemptively downloading multiple VPNs in case the one or more are blocked or fail.

Who is doing what?

Identifying the process by which internet restrictions are put in place can reveal whether the government, the internet service provider, or some other actor was responsible. Complicating matters, however, is that governments often initially deny any involvement.

Orders to ISPs

For a government to implement restrictions on network connectivity or social media, it usually requires the compliance of ISPs.

Internet providers take a financial hit when the population can’t use their services so why do they comply? Often the answer is fear of retribution or legal consequences, including the loss of their operating licenses or even prosecution of their executives.

During the network shutdown during the 2018 election in the DRC, internet provider Global texted customers explaining that the government ordered a network shutdown. Vodacom told reporters the same thing.

Service providers in the DRC have been similarly transparent in the face of shutdown requests in the past, citingtheir legal obligation to comply.

Government-controlled infrastructure

In certain cases, there is no need for the government to go through private-sector middlemen when it wants to restrict connectivity. This is the case in Ethiopia, where the government has a monopoly on the country’s telecommunications infrastructure. EthioTelecom, the sole provider in the country, is state-owned. This type of centralisation enables the government to restrict internet access at will

What’s the point?

Governments justify internet freedom violations in a number of ways, but there are a few common triggers.

Protests

Already in 2019, protests have prompted restrictions in a number of countries including Sudan, Liberia, and Zimbabwe. Social media are powerful organising tools so some governments see restrictions on them as a way to tamp down popular mobilisation.

Limiting communication can also prevent the spread of news about the state’s human rights violations. This reasoning was cited as a concern in Zimbabwe and Sudan.

Unfavourable news

When the Chadian government blocked social media beginning on 28 March, 2018, it was not in response to a particular external catalyst. Instead, the authorities were reacting to a constitutional reform proposal that would allow the long-time president to serve additional terms in office. The blocking was apparently an attempt to prevent protests or other backlash against the plan, which was likely to be unpopular.

Exams

Shutting down the internet during exams may seem comparatively innocuous, but it is a disproportionate response to the risk of cheating and sets a precedent for abuse in the future. Algeria has made a habit of exam-related shutdowns as has Ethiopia, most recently in June.

Elections

Elections are a flashpoint for other internet freedom violations, so it is no surprise that some elections have been accompanied by social media blocks or network shutdowns in the last few years. This year began with the internet being disconnected in the DRC following a disputed presidential election in late December. A few months later, service was shut down on election day in Benin. The latter case was seen as more of a surprise, as Benin has generally been considered one of the more reliable democracies in Africa.

Why this matters

A 2015 UN joint declaration asserted that network shutdowns “can never be justified under human rights law.”

No matter the type of restriction, how it was enacted, or what reasoning is provided, wholesale internet disruptions and social media blocking are never worth the problems they cause.

Even supposed national security concerns and the fight against “fake news” do not outweigh the very real consequences of cutting off access to information for millions of people.

Network and social media restrictions limit freedom of the press and freedom of speech, and can entail enormous economic costs. In the case of the DRC, UN special rapporteur for freedom of expression David Kaye echoed the 2015 UN declaration, calling the country’s shutdown “a clear violation of international law.”

He also pointed out that the shutdown undermined electoral integrity and damaged people’s access to basic services. Perhaps most importantly, such violations deprive individuals of the ability to communicate with friends and family, often at a time when public safety may be compromised.

If they are concerned about maintaining order at sensitive moments, governments operating in good faith would do better to increase transparency, encourage the dissemination of accurate information, actively debunk falsehoods, and directly address the grievances that might lead to criticism or unrest in the first place.

This article was first published by African Arguments July 24, 2019.

Analyses and recommendations offered by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of Freedom House.