Mto Songwe

JF-Expert Member

- Jul 17, 2023

- 6,016

- 12,303

The Washington-Beijing tech war is just getting started

U.S. commerce chief takes a hard line with China but will it have an impact?

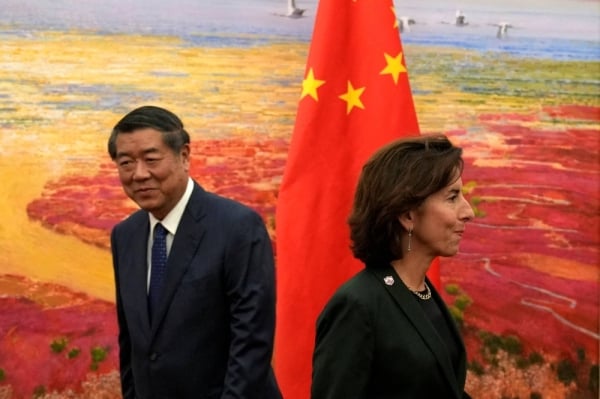

U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng meet for talks in Beijing on Aug. 29. | REUTERS

BY BRAD GLOSSERMAN

CONTRIBUTING WRITER

SHARE

Dec 12, 2023

U.S. secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo didn’t get the memo.

Fireside chats are supposed to be avuncular, intimate conversations that inform and sooth the audience. Instead, in remarks last week to the Reagan National Defense Forum and in a subsequent interview with CNBC, Raimondo issued grim warnings about geopolitical and technological competition with China and steps that the U.S. is prepared to take to protect itself in that race.

Observers said that her comments “felt like a turning point” and mark the birth of “dark Gina.” While Raimondo doesn’t make the U.S. government’s tech policy, her department is instrumental in crafting and enforcing laws and regulations when that shuddering behemoth does reach consensus. Her remarks are a warning to U.S. businesses, China and American allies and partners that change is coming. The U.S. is taking a harder line on technology controls.

The Reagan National Defense Forum is the premier national security event for Republican internationalists, a rallying point for old-school hawks. It is an indication of the shifting political center of gravity on security issues that Biden administration officials such as Raimondo and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin were among the most prominent speakers at the event.

Raimondo’s logic is simple: The threat from China is large and growing and technology is central to the evolution and maturation of its military capabilities. The U.S. has to ensure that it isn’t aiding that development and tech controls are designed to do that. “Our national defense is more than guns, missiles, tanks and drones. It’s technology, it’s innovation, it’s working with our allies,” she said.

“We cannot let them catch up, so we are going to deny them our most cutting-edge technology,” she added. More bluntly still, “We can’t let China get these chips. Period.”

She went on to note, however, that “it’s not realistic” to think the U.S. can stop China’s technological development, but it can “slow them down.” Companies can continue to do business with China but they can’t sell “the most sophisticated, cutting edge artificial intelligence chips.”

Raimondo’s position has hardened; part of the trajectory is personal. She was in Beijing for talks last summer when Huawei released a new phone that observers believe was based on technology that managed to evade controls the U.S. government — her office — had imposed. The slight was clear: The phone debuted “when I was in China, thank you very much,” she said.

Raimondo was clear, too, that trade controls introduced in October of 2022 and modified a year later are only the beginning. “We have to change constantly,” she told CNBC. “Technology changes, China changes and we have to keep up with it.”

She is establishing “a continuous dialogue” between government and business to ensure that gaps don’t emerge either as a result of breakthroughs, deliberate attempts to work around controls by redesigning chips, as appears to be happening, or the establishment of new companies to get around end-user restrictions. Raimondo complained that “It’s a constant whack-a-mole. ... We put them on the list and literally a week from now there’ll be another company, or China will create another subsidiary.”

There is also concern that allies and partners might not join U.S. restrictions, undercutting their effectiveness. This is why Washington pressed hard on Japan and the Netherlands to impose similar controls on the export of semiconductor manufacturing equipment last year — which they eventually did.

Business isn’t happy. Companies worry about losing markets and losing money, with Nvidia, a large U.S. manufacturer, complaining that U.S. restrictions could cost it $400 million in sales annually.

China too is unhappy. Wang Wenbin, a spokesperson for the Chinese Foreign Ministry, accused “certain individuals” in the U.S. of harboring a “deep-rooted Cold War mentality.” The relationship with China could suffer, he warned. Moreover, controls won’t work. Citing the Global Times, a nationalist tabloid, Wang pronounced that “Going against the principles and laws of the free trade market is like building a dam with a sieve. No matter how hard you try, water will still find its way through the gaps and flow where it should.”

Raimondo isn’t deterred, however, and that means this process is just getting started. Semiconductors are merely the first items on the list of new and emerging technologies considered vital to national economic health and security. That prominence reflects their obvious and critical role, and, perhaps most important, the fact that they already exist.

Many of the other technologies are still being developed and their uses and applications are only emerging. Raimondo has said that the U.S. is now looking at the “most sophisticated AI and all the products that flow from that,” as well as biotechnology and quantum computing.

Chip controls have impacts in those fields, too, which is why ongoing dialogue is needed. Most semiconductors have specialized functions. Rest assured that chips designed for other technologies will be restricted as well.

But not just the chips — note Raimondo’s reference to “products.” The Biden administration could take a page from the Huawei experience and ban Chinese AI from its critical infrastructure and demand that its allies do the same.

In this case, the main concern isn’t the possibility of inserting a kill switch or accessing data running through the system — although both remain — but the information and insight that can be gleaned from meta-analysis of the system’s operations.

Last week, IBM released papers that showed progress in quantum computing, demonstrating that with “large enough systems, capable enough systems, that you can do useful technical and scientific work with (quantum),” explained Dario Gil, head of research at IBM. Business applications remain a distant dream, but the results are encouraging.

The prospect of useful quantum computing means that the U.S. and its allies are going to try to control access to that technology, especially given fears that it can crack RSA encryption, the world’s most widely used cryptography system, one that has been adopted by governments, tech companies and financial institutions. If that happens, much of the world’s most protected information would be secret no more.

Then there’s biotech, another field that will have a profound impact on economies and societies. Geopolitical considerations already weigh on biotech investment: U.S. venture capital investment in Chinese firms has reportedly fallen by 50% because of fears of increasing U.S. government scrutiny and eventual regulation.

In a recent conversation, one expert predicted that the U.S. would move down a laundry list of technologies, from most important to least important, which would result in the decoupling of the two economies — and ask friends and partners to go along with it.

There is one big problem with tightening restrictions: The policy assumes the U.S. leads in the various fields. Unfortunately, according to the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s Technology Tracker, China leads in 53 of 64 critical and emerging technologies; the U.S. is ahead in the other 11.

Among the areas in which China is on top are biotechnology advances, which include synthetic biology, biological manufacturing, genome and genetic sequencing and analysis, and novel antibiotics and antivirals; post-quantum cryptography, quantum communications and quantum sensors; and, in the field of AI, advanced data analytics, algorithms and hardware accelerators, adversarial AI and machine learning.

If its analysis is correct, Raimondo’s hard line won’t have much impact on China’s pursuit of new technologies. If the stakes in this competition are as high as I believe they are, however, the U.S. and its allies must err on the side of caution, which means continuing with its tech restrictions and supercharging efforts to promote innovation. That should be the focus of Raimondo’s next fireside chat

Article by theJapantimes