Informer

JF-Expert Member

- Jul 29, 2006

- 1,599

- 6,669

The Economist - April 10, 2017

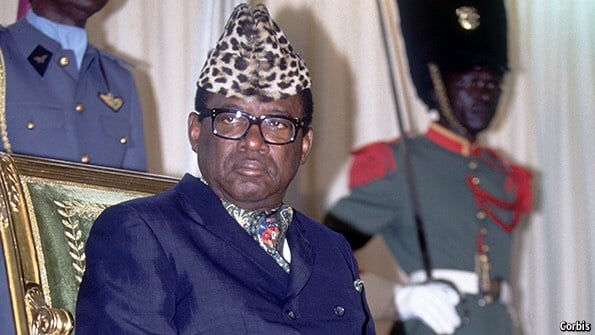

MOBUTU SESE SEKO, who ruled Congo for 32 years, was notorious for his “musical chairs” approach to his cabinet. His deputies were constantly shuffled around, passing unpredictably from ministerial posts to prison and exile, before once again returning to high office. Over the course of his reign Mr Mobutu burned through hundreds of ministers. High ministerial turnover is common to many dictatorships, as a study of 15 African countries shows. Why are dictators so fickle with their cabinets, and how can ministers avoid being sacked, or worse?

In a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Patrick Francois and Francesco Trebbi of the University of British Columbia and Ilia Rainer of George Mason University modelled the autocrat’s dilemma of choosing which ministers he should hire to run his government. Experienced ministers are better able to help manage the country, as you would expect. But time in power also allows them to develop their own political base which, if left unchecked, could give them the means to launch a coup. Thus a dictator who wishes to avoid being overthrown must fire ministers before they accumulate enough support to topple him. In turn, ministers who manage to build their own independent support bases must decide whether they are better off remaining loyal to the current regime or attempting to overthrow it.

The time of maximum danger for ministers, it turns out, is four years into the job. In the first few years of a ministerial career they are not powerful enough to pose much of a threat. And once they have racked up lots of experience they have little incentive to rock the boat, as they would be risking a safe position for the uncertain gains from an attempted coup. But with four years under their belts they are most dangerous: just powerful enough to have a chance at the main prize, but not yet so well established as to have lost their hunger. So it is then that dictators’ ministers are most likely to find themselves bundled into jail.

The authors show that those most at risk are the most senior ministers, such as those in charge of defence or finance. Those ministers’ superior powers make them especially threatening. So those posts change hands a lot—ruinously for the country’s economy and armed forces. The policy of firing ministers just as they begin to acquire experience on the job seriously degrades dictators’ ability to govern. But for a despot who values his own survival above all else, ministerial incompetence has a lot to recommend it—something worth bearing in mind if you want to get ahead under a dictatorship.

Dig deeper:

The last days of Mobutu Sese Seko (May 1997)

With rebel fighters on the back foot, optimism is growing in Congo (March 2014)

How and why lofty ideologies cohabit with rampant corruption (July 2014)

MOBUTU SESE SEKO, who ruled Congo for 32 years, was notorious for his “musical chairs” approach to his cabinet. His deputies were constantly shuffled around, passing unpredictably from ministerial posts to prison and exile, before once again returning to high office. Over the course of his reign Mr Mobutu burned through hundreds of ministers. High ministerial turnover is common to many dictatorships, as a study of 15 African countries shows. Why are dictators so fickle with their cabinets, and how can ministers avoid being sacked, or worse?

In a working paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research, Patrick Francois and Francesco Trebbi of the University of British Columbia and Ilia Rainer of George Mason University modelled the autocrat’s dilemma of choosing which ministers he should hire to run his government. Experienced ministers are better able to help manage the country, as you would expect. But time in power also allows them to develop their own political base which, if left unchecked, could give them the means to launch a coup. Thus a dictator who wishes to avoid being overthrown must fire ministers before they accumulate enough support to topple him. In turn, ministers who manage to build their own independent support bases must decide whether they are better off remaining loyal to the current regime or attempting to overthrow it.

The time of maximum danger for ministers, it turns out, is four years into the job. In the first few years of a ministerial career they are not powerful enough to pose much of a threat. And once they have racked up lots of experience they have little incentive to rock the boat, as they would be risking a safe position for the uncertain gains from an attempted coup. But with four years under their belts they are most dangerous: just powerful enough to have a chance at the main prize, but not yet so well established as to have lost their hunger. So it is then that dictators’ ministers are most likely to find themselves bundled into jail.

The authors show that those most at risk are the most senior ministers, such as those in charge of defence or finance. Those ministers’ superior powers make them especially threatening. So those posts change hands a lot—ruinously for the country’s economy and armed forces. The policy of firing ministers just as they begin to acquire experience on the job seriously degrades dictators’ ability to govern. But for a despot who values his own survival above all else, ministerial incompetence has a lot to recommend it—something worth bearing in mind if you want to get ahead under a dictatorship.

Dig deeper:

The last days of Mobutu Sese Seko (May 1997)

With rebel fighters on the back foot, optimism is growing in Congo (March 2014)

How and why lofty ideologies cohabit with rampant corruption (July 2014)