mchambawima1

JF-Expert Member

- Oct 16, 2014

- 2,487

- 738

A sharp-eyed look at contemporary Africa

The Rift: A New Africa Breaks Free. By Alex Perry. Little, Brown; 448 pages; $30. Weidenfeld & Nicolson; 320 pages; £20.

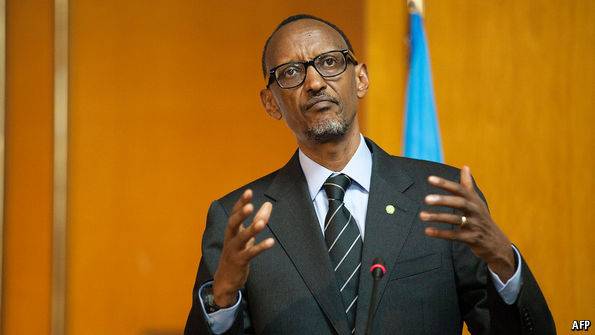

FEW African leaders arouse such divided opinions as Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda since 2000 but its de facto leader since 1994, when his Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group, seized power and ended the country’s genocide. For many observers Mr Kagame is an ascetic, an austere moderniser who has pulled his country back from its descent into barbarism and overseen reforms aimed at improving its governance and boosting the economy.

Critics contend that his forces have killed thousands of people and that his government ruthlessly suppresses opposition, murdering dissidents both at home and abroad. For Alex Perry, who spent time with Mr Kagame while he was Africa bureau chief for Time magazine, neither of these Manichean views is quite right; nor are they quite wrong. After confronting Mr Kagame with allegations that his rebel forces had killed 25,000 people in reprisal massacres after the genocide, the president “growled that the real story was how many people the RPF didn’t kill,” Mr Perry writes. “We had to battle extreme anger among our own men,” he quotes Mr Kagame as saying. “So many had lost their families and they had guns in their hands. Whole villages could have been wiped out. But we did not allow it.”

Mr Perry’s ability to capture the complexities of stories in which there are no clear heroes nor outright villains echoes again and again through his latest book, “The Rift”. Written with a clear eye after criss-crossing the continent, he offers telling glimpses of an Africa that defies stereotyping. The author is at his strongest when he describes just how many people have done Africa a disservice, even when setting out to help. He stands in the ruins of the Somali capital, Mogadishu, talking to a mother whose child dies of malnutrition before his eyes; the famine was largely caused by Western governments blocking the flow of food aid to Somalia in the belief that this would weaken the grip of the Shabab, a jihadist group.

In another chapter Mr Perry describes how United Nations (UN) peacekeepers working in South Sudan shuffle paperwork in air-conditioned bungalows or jog around their sprawling camps wearing Lycra, while outside the gates large bulldozers are shovelling bodies into mass graves. “They saved our lives late,” says one refugee who described repeated rebel attacks on a refugee camp just a few minutes away from a large UN base whose peacekeepers did not venture out. “They did not risk until it became peaceful.”

Yet the clarity of Mr Perry’s reporting, which is reason enough to read his book, is not matched by the metaphor of “The Rift”. The book revolves around the idea that, much as a new continent is slowly cleaving itself away from the rest along the Rift Valley, so too a new Africa is being born from the old. Aside from a few pages at the end where Mr Perry writes of African innovations, including ways of reversing desertification, the book does not quite live up to its promise.

The Rift: A New Africa Breaks Free. By Alex Perry. Little, Brown; 448 pages; $30. Weidenfeld & Nicolson; 320 pages; £20.

FEW African leaders arouse such divided opinions as Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda since 2000 but its de facto leader since 1994, when his Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a rebel group, seized power and ended the country’s genocide. For many observers Mr Kagame is an ascetic, an austere moderniser who has pulled his country back from its descent into barbarism and overseen reforms aimed at improving its governance and boosting the economy.

Critics contend that his forces have killed thousands of people and that his government ruthlessly suppresses opposition, murdering dissidents both at home and abroad. For Alex Perry, who spent time with Mr Kagame while he was Africa bureau chief for Time magazine, neither of these Manichean views is quite right; nor are they quite wrong. After confronting Mr Kagame with allegations that his rebel forces had killed 25,000 people in reprisal massacres after the genocide, the president “growled that the real story was how many people the RPF didn’t kill,” Mr Perry writes. “We had to battle extreme anger among our own men,” he quotes Mr Kagame as saying. “So many had lost their families and they had guns in their hands. Whole villages could have been wiped out. But we did not allow it.”

Mr Perry’s ability to capture the complexities of stories in which there are no clear heroes nor outright villains echoes again and again through his latest book, “The Rift”. Written with a clear eye after criss-crossing the continent, he offers telling glimpses of an Africa that defies stereotyping. The author is at his strongest when he describes just how many people have done Africa a disservice, even when setting out to help. He stands in the ruins of the Somali capital, Mogadishu, talking to a mother whose child dies of malnutrition before his eyes; the famine was largely caused by Western governments blocking the flow of food aid to Somalia in the belief that this would weaken the grip of the Shabab, a jihadist group.

In another chapter Mr Perry describes how United Nations (UN) peacekeepers working in South Sudan shuffle paperwork in air-conditioned bungalows or jog around their sprawling camps wearing Lycra, while outside the gates large bulldozers are shovelling bodies into mass graves. “They saved our lives late,” says one refugee who described repeated rebel attacks on a refugee camp just a few minutes away from a large UN base whose peacekeepers did not venture out. “They did not risk until it became peaceful.”

Yet the clarity of Mr Perry’s reporting, which is reason enough to read his book, is not matched by the metaphor of “The Rift”. The book revolves around the idea that, much as a new continent is slowly cleaving itself away from the rest along the Rift Valley, so too a new Africa is being born from the old. Aside from a few pages at the end where Mr Perry writes of African innovations, including ways of reversing desertification, the book does not quite live up to its promise.