Babylon

JF-Expert Member

- Feb 5, 2009

- 1,332

- 82

[h=1]Britain 1947: Poverty, queues, rationing - and resilience[/h] Britain was a nation in desperate need of cheering up - getting out the bunting, having a knees-up - in 1947, the year that the smiling, 21-year-old Princess Elizabeth married her Prince Charming.

The country was beset by the gloom of winning a war heroically and then having to settle for a peacetime that was drab, impoverished and anything but glorious.

The fighting spirit that had kept the country battling on from 1939 to 1945 was all but gone two years later, drained away for most people via a lack of everything: food, adequate housing, money and prospects.

The only things in abundance were rationing coupons - for meat, butter, lard, margarine, sugar, tea, cheese, soap, clothing, petrol, sweets... the list was endless.

Scroll down for more...

Tightening belts: Despite the end of the war rationing squeezes ever harder

Tightening belts: Despite the end of the war rationing squeezes ever harder

It went against the grain to have to swallow this state of affairs. "I didn't mind doing it in the war," one housewife recalled. "I used to look upon 'making do' as a national duty and make a game of it."

Now it was "tiresome".

But she and millions like her still carried on with that game, however unwelcome and depressing it was. They would "make do and mend". They would not go under, though it was a perilously close call.

After years of war, continued rationing was a terrible blow. Even when you did get your hands on a prized morsel, it was rarely a delicacy worth eating.

In her diary, another housewife summed up her miserable dinner: two sausages which tasted like wet bread with sage added, mashed potato made from powder, half a tomato, one cube of cheese, and one slice of bread and butter.

The bag of coal she bought for 4s 10d was full of slate and stone. "But at least we're not being bombed," she added, finding a cheery note among the bad news.

Her own daughter was also engaged and the family had managed to have a small party. She worried for the young couple, however. "I am wondering how long it will be before they can afford to marry, with prices so high."

Scroll down for more...

Coal comfort: These women celebrate the coup of having got a good batch of coal

Coal comfort: These women celebrate the coup of having got a good batch of coal

All this misery came after the hardest winter in living memory, with 20ft-high snowdrifts in the countryside, and villages and towns cut off.

Then there had been power cuts and short-time working for millions as electricity stations closed for lack of coal. The government adopted emergency powers over a country that felt itself not at peace but under siege.

Between the announcement of the Princess's engagement in July and the wedding in November, things worsened for most people beyond the bounds of Buckingham Palace.

The weekly ration of meat from the butcher had been chopped to one shilling's worth, by law petrol was available only for essential motoring not for pleasure, and holidaying abroad was banned.

Worse still, potatoes were on the restricted list for the first time.

We had fought Hitler for six years and had our fill of spuds, but now the national dish - chips - was threatened. Not that it mattered, because the only fish within the reach of most people's pockets was a nasty, oily import from South Africa called snoek.

But what was really bringing the country to its knees was the end of American support.

It wasn't just Britain's fighting spirit that had dried up. More disturbingly, so had the flood of cash and commodities from across the Atlantic to fuel the war. The tap had been turned off.

The new Labour government was under pressure to make Britain live within its means and to start paying off the huge debts amassed during the war.

The Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was gloomy: "I have no easy words for the nation. I cannot say when we will emerge into easier times."

From Washington, Mrs Roosevelt, the former President's wife had sent towels as a present to the young royal couple, but it would take more than that to clean up the mess Britain was in.

Scroll down for more...

Form an orderly queue: Sights like this were the norm after the withdrawal of U.S. aid hit general supplies

Form an orderly queue: Sights like this were the norm after the withdrawal of U.S. aid hit general supplies

You had only to look around to see the drabness. A newcomer to London was appalled at, "public buildings filthy and pitted with shrapnel scars running with pigeon dung.

"Bus tickets and torn newspapers blew down the streets: whole suburbs of private houses were peeling, cracking, their windows unwashed, their steps unswept, their gardens untended." He thought London "a decaying, decrepit, sagging, rotten city".

It is hard for us to grasp now how badly Britain had emerged from the war, bombed out, exhausted and now bankrupt. Housing was a disgrace.

Proud men who had fought their way from Normandy to Germany came back to find themselves with no home of their own, living in squalid lets or forced to lodge with in-laws.

To get to the top of the council list and be allocated a pre-fab - a temporary single-storey home - was heaven.

For many, peacetime was difficult to adjust to. Demobbed servicemen were pushed to the back of the queue for jobs, overtaken by those who had missed the fighting. And, anyway, what job was there in civilian life to fulfil the expectations of a bomber pilot or a front-line sergeant-major?

Home life was also hard to come to terms with after years away. Wives and children might resent the returning "stranger" back from the war.

Domestic violence increased; divorces doubled in three years - though the actual numbers were small and they were still very much the exception. A broken marriage was a cause for stigma, not treated with a sigh as today.

Scroll down for more...

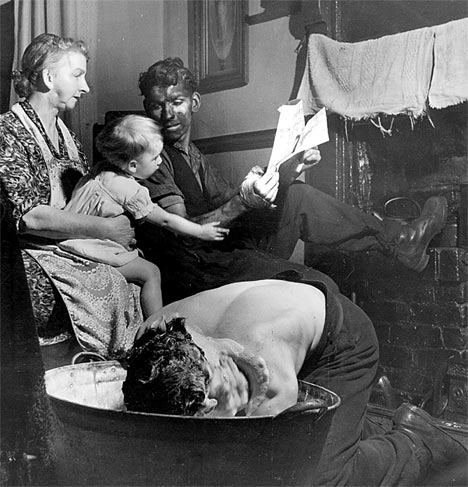

Diamond geezer: A coal miner waits his turn in the family's tin bath

Diamond geezer: A coal miner waits his turn in the family's tin bath

There was a discernible trend of lawlessness (house-breaking, vandalism and the like) among boys who had grown up without the presence of their fathers.

But the vast majority of families battled on and made the best of their circumstances. You could "make do and mend" a marriage as well as a meal or a change of clothing.

The hardships of war, military discipline, and the loss of comrades and loved ones had made them stoical, more accepting of their lot. But it had also made them resilient, tougher men and women in the face of adversity.

It was this tired nation that summoned up all its energy to celebrate a royal wedding. From some quarters, predictably perhaps, came revolutionary warnings.

"Any banqueting and display of wealth at your daughter's wedding will be an insult to the British people at the present time," railed the Camden Town branch of the Amalgamated Society Of Woodworkers. "You would be well advised to order a very quiet wedding in keeping with the times."

There would be no such thing. Prince Philip had not one but two stag parties, the cake was 9ft high in four tiers and weighed 500lb, the bridal dress was an exquisite, flowing gown. There was no sign of austerity in the celebrations. Dressed in their finery, the 2,000-plus guests appeared a coupon-free zone.

But it did not seem to matter. The general consensus, as one commentator put it, was that this was "the love match it is claimed to be and we are glad about it. And Philip was easy on the eye, the sort any young girl would fall in love with."

With no televisions - and the very idea of such a device beyond the imagination of most people - this was an event to listen to.

In their millions, the British people crowded around their Bakelite radios, at home or at work (if they were allowed, that is, by bosses less flexible than today), to listen to the service.

And in their hundreds of thousands, people poured on to the streets of London, jamming Trafalgar Square, Whitehall and The Mall.

They had only demob suits and women's utility clothes to wear, poorly made and loose-fitting in scratchy, cheap fabrics. No matter that over the Channel in Paris, Christian Dior was wheeling out his New Look of shaped and luxuriant dresses.

In London they stood, sometimes drenched by heavy showers of rain, waiting, community singing, chatting, arguing, just as they had done while sheltering from air raids in the Underground during the war.

Waiting was something the nation had become good at. In post-war Britain the shortages were such that people queued for everything. There were long lines in the street that a generation later we would associate with Communist Eastern Europe. The shortages made it inevitable.

But the queues were orderly, unlike the scrums in even the most fully stocked stores these days. Manners prevailed. Men were "Mr" and young girls "Miss", and gentlemen raised their hats to ladies.

The night before the royal wedding, Londoners brought out the mattresses and blankets that they had used in their cellars and under the stairs during the Blitz and stored away hoping never to use them again.

Now, they were laid down to soften the flagstone pavements on the route the royal procession would take.

The women brought vacuum flasks filled with warm water to wash their faces in the morning and then put on fresh make-up. It would not be right to be pale and unadorned as the fairytale Princess went by.

After the wedding in Westminster Abbey, the crowds swarmed down The Mall and yelled for the Royal Family to come on to the balcony. And not just the newlyweds, whose presence denoted a brighter future for everyone.

The crowd's biggest cries were for the King, just as they had shouted for him on VE night. It was as if they wanted to remind themselves of how good that day of victory had been and how much they would pull together to get out of the present mire.

The country did, indeed, pull itself round, though it would take a decade.

Life in 1947 may have been utterly threadbare and unrecognisable compared with the Britain in which the now Queen Elizabeth II is celebrating her 60th wedding anniversary.

No supermarkets, no lager, no vinyl, no CDs, no washing machines or even refrigerators, except on American airbases, as David Kynaston says in his fascinating book, Austerity Britain.

This was a Britain to yearn for in some ways - one of corner shops and leaf tea not teabags, red telephone boxes not iphones, quaint Austin Sevens and Ford Eights not SUVs and BMWs, of words in full (as from the announcer who each day heralded "the British Broadcasting Corporation") not initials, of grammar not text-speak.

It was also a Britain of smog in the cities and chilblains for children clustering round coal fires. No central heating but fewer allergies. New fears about the emerging Soviet Union but no global warming and no global terrorism.

It was a Britain to which prosperity would return, though not necessarily with the same selfless spirit that got people though the years of post-war hardship.

Those lining the streets and listening in on their radios could never have conceived of the wealth and material satisfaction that lay ahead for the next generation.

Sixty years would change Britain utterly from a land of Woodbines and beer to cocktails and cocaine. Whether we lost something along the way is quite another matter.

The country was beset by the gloom of winning a war heroically and then having to settle for a peacetime that was drab, impoverished and anything but glorious.

The fighting spirit that had kept the country battling on from 1939 to 1945 was all but gone two years later, drained away for most people via a lack of everything: food, adequate housing, money and prospects.

The only things in abundance were rationing coupons - for meat, butter, lard, margarine, sugar, tea, cheese, soap, clothing, petrol, sweets... the list was endless.

Scroll down for more...

It went against the grain to have to swallow this state of affairs. "I didn't mind doing it in the war," one housewife recalled. "I used to look upon 'making do' as a national duty and make a game of it."

Now it was "tiresome".

But she and millions like her still carried on with that game, however unwelcome and depressing it was. They would "make do and mend". They would not go under, though it was a perilously close call.

After years of war, continued rationing was a terrible blow. Even when you did get your hands on a prized morsel, it was rarely a delicacy worth eating.

In her diary, another housewife summed up her miserable dinner: two sausages which tasted like wet bread with sage added, mashed potato made from powder, half a tomato, one cube of cheese, and one slice of bread and butter.

The bag of coal she bought for 4s 10d was full of slate and stone. "But at least we're not being bombed," she added, finding a cheery note among the bad news.

Her own daughter was also engaged and the family had managed to have a small party. She worried for the young couple, however. "I am wondering how long it will be before they can afford to marry, with prices so high."

Scroll down for more...

All this misery came after the hardest winter in living memory, with 20ft-high snowdrifts in the countryside, and villages and towns cut off.

Then there had been power cuts and short-time working for millions as electricity stations closed for lack of coal. The government adopted emergency powers over a country that felt itself not at peace but under siege.

Between the announcement of the Princess's engagement in July and the wedding in November, things worsened for most people beyond the bounds of Buckingham Palace.

The weekly ration of meat from the butcher had been chopped to one shilling's worth, by law petrol was available only for essential motoring not for pleasure, and holidaying abroad was banned.

Worse still, potatoes were on the restricted list for the first time.

We had fought Hitler for six years and had our fill of spuds, but now the national dish - chips - was threatened. Not that it mattered, because the only fish within the reach of most people's pockets was a nasty, oily import from South Africa called snoek.

But what was really bringing the country to its knees was the end of American support.

It wasn't just Britain's fighting spirit that had dried up. More disturbingly, so had the flood of cash and commodities from across the Atlantic to fuel the war. The tap had been turned off.

The new Labour government was under pressure to make Britain live within its means and to start paying off the huge debts amassed during the war.

The Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, was gloomy: "I have no easy words for the nation. I cannot say when we will emerge into easier times."

From Washington, Mrs Roosevelt, the former President's wife had sent towels as a present to the young royal couple, but it would take more than that to clean up the mess Britain was in.

Scroll down for more...

You had only to look around to see the drabness. A newcomer to London was appalled at, "public buildings filthy and pitted with shrapnel scars running with pigeon dung.

"Bus tickets and torn newspapers blew down the streets: whole suburbs of private houses were peeling, cracking, their windows unwashed, their steps unswept, their gardens untended." He thought London "a decaying, decrepit, sagging, rotten city".

It is hard for us to grasp now how badly Britain had emerged from the war, bombed out, exhausted and now bankrupt. Housing was a disgrace.

Proud men who had fought their way from Normandy to Germany came back to find themselves with no home of their own, living in squalid lets or forced to lodge with in-laws.

To get to the top of the council list and be allocated a pre-fab - a temporary single-storey home - was heaven.

For many, peacetime was difficult to adjust to. Demobbed servicemen were pushed to the back of the queue for jobs, overtaken by those who had missed the fighting. And, anyway, what job was there in civilian life to fulfil the expectations of a bomber pilot or a front-line sergeant-major?

Home life was also hard to come to terms with after years away. Wives and children might resent the returning "stranger" back from the war.

Domestic violence increased; divorces doubled in three years - though the actual numbers were small and they were still very much the exception. A broken marriage was a cause for stigma, not treated with a sigh as today.

Scroll down for more...

There was a discernible trend of lawlessness (house-breaking, vandalism and the like) among boys who had grown up without the presence of their fathers.

But the vast majority of families battled on and made the best of their circumstances. You could "make do and mend" a marriage as well as a meal or a change of clothing.

The hardships of war, military discipline, and the loss of comrades and loved ones had made them stoical, more accepting of their lot. But it had also made them resilient, tougher men and women in the face of adversity.

It was this tired nation that summoned up all its energy to celebrate a royal wedding. From some quarters, predictably perhaps, came revolutionary warnings.

"Any banqueting and display of wealth at your daughter's wedding will be an insult to the British people at the present time," railed the Camden Town branch of the Amalgamated Society Of Woodworkers. "You would be well advised to order a very quiet wedding in keeping with the times."

There would be no such thing. Prince Philip had not one but two stag parties, the cake was 9ft high in four tiers and weighed 500lb, the bridal dress was an exquisite, flowing gown. There was no sign of austerity in the celebrations. Dressed in their finery, the 2,000-plus guests appeared a coupon-free zone.

But it did not seem to matter. The general consensus, as one commentator put it, was that this was "the love match it is claimed to be and we are glad about it. And Philip was easy on the eye, the sort any young girl would fall in love with."

With no televisions - and the very idea of such a device beyond the imagination of most people - this was an event to listen to.

In their millions, the British people crowded around their Bakelite radios, at home or at work (if they were allowed, that is, by bosses less flexible than today), to listen to the service.

And in their hundreds of thousands, people poured on to the streets of London, jamming Trafalgar Square, Whitehall and The Mall.

They had only demob suits and women's utility clothes to wear, poorly made and loose-fitting in scratchy, cheap fabrics. No matter that over the Channel in Paris, Christian Dior was wheeling out his New Look of shaped and luxuriant dresses.

In London they stood, sometimes drenched by heavy showers of rain, waiting, community singing, chatting, arguing, just as they had done while sheltering from air raids in the Underground during the war.

Waiting was something the nation had become good at. In post-war Britain the shortages were such that people queued for everything. There were long lines in the street that a generation later we would associate with Communist Eastern Europe. The shortages made it inevitable.

But the queues were orderly, unlike the scrums in even the most fully stocked stores these days. Manners prevailed. Men were "Mr" and young girls "Miss", and gentlemen raised their hats to ladies.

The night before the royal wedding, Londoners brought out the mattresses and blankets that they had used in their cellars and under the stairs during the Blitz and stored away hoping never to use them again.

Now, they were laid down to soften the flagstone pavements on the route the royal procession would take.

The women brought vacuum flasks filled with warm water to wash their faces in the morning and then put on fresh make-up. It would not be right to be pale and unadorned as the fairytale Princess went by.

After the wedding in Westminster Abbey, the crowds swarmed down The Mall and yelled for the Royal Family to come on to the balcony. And not just the newlyweds, whose presence denoted a brighter future for everyone.

The crowd's biggest cries were for the King, just as they had shouted for him on VE night. It was as if they wanted to remind themselves of how good that day of victory had been and how much they would pull together to get out of the present mire.

The country did, indeed, pull itself round, though it would take a decade.

Life in 1947 may have been utterly threadbare and unrecognisable compared with the Britain in which the now Queen Elizabeth II is celebrating her 60th wedding anniversary.

No supermarkets, no lager, no vinyl, no CDs, no washing machines or even refrigerators, except on American airbases, as David Kynaston says in his fascinating book, Austerity Britain.

This was a Britain to yearn for in some ways - one of corner shops and leaf tea not teabags, red telephone boxes not iphones, quaint Austin Sevens and Ford Eights not SUVs and BMWs, of words in full (as from the announcer who each day heralded "the British Broadcasting Corporation") not initials, of grammar not text-speak.

It was also a Britain of smog in the cities and chilblains for children clustering round coal fires. No central heating but fewer allergies. New fears about the emerging Soviet Union but no global warming and no global terrorism.

It was a Britain to which prosperity would return, though not necessarily with the same selfless spirit that got people though the years of post-war hardship.

Those lining the streets and listening in on their radios could never have conceived of the wealth and material satisfaction that lay ahead for the next generation.

Sixty years would change Britain utterly from a land of Woodbines and beer to cocktails and cocaine. Whether we lost something along the way is quite another matter.