BAK

JF-Expert Member

- Feb 11, 2007

- 124,789

- 288,015

A test of convictions

First of two parts

By Stephanie Chen, CNN

October 26, 2009 9:17 a.m. EDT

Chicago, Illinois (CNN) -- For Jewel Mitchell, it was the worst Christmas of her life, the pain so raw she secluded herself in her bedroom to shield her two young daughters.

It was 1996, and the man she was supposed to marry - the man her girls idolized - had already been gone two years. But this Christmas, he was supposed to come home and pick up where they had left off:

Walking Latoni and Latoya to school. Playing Chutes and Ladders with them on Friday nights. Taking their mother on dates to the lakefront to watch the waves of Lake Michigan dance.

But Jewel's fiancé wasn't returning to their home on Chicago's South Side. Five days earlier, Dean Cage, had been sentenced to 40 years in prison for an aggravated sexual assault he said he didn't commit. Jewel was his alibi. At the time of the attack, she said, he was asleep next to her.

The day they'd planned to marry had come and gone with Dean in the Cook County Jail, unable to afford bond set at half a million dollars. When his trial date finally arrived -- just two months before this miserable Christmas -- Jewel listened to a young girl describe the man who brutally attacked her as she walked to her bus stop on a dark November morning. She was just 15.

Reporting of story

The scenes in this two-part story span more than 14 years and were reconstructed through interviews, court documents and letters.

CNN writer Stephanie Chen interviewed Jewel Mitchell and Dean Cage and their attorneys and family members. Among the documents she reviewed were Cage's trial transcript and the Innocence Project's file on Cage.

The quotes in the story are drawn from interviews or documents. The thoughts of the subjects, or the words they recall speaking or hearing, appear in italic.

Those were difficult days for Jewel, but at least then she could still cling to the hope that the world would soon learn what she knew without a doubt: This was a case of mistaken identity.

On the day of the verdict, family and co-workers packed the courtroom to support a man who'd never been arrested before in his life. Jewel wore her best navy pantsuit and told her older brother: Today, my fiancé is coming home.

But the truth did not prevail. Two years after being arrested, Dean was declared guilty, and Jewel's optimism was drained away, her hope annihilated.

She would put on a happy face to celebrate the holiday with her daughters. But the Christmas gifts she'd bought Dean, a boom box and a pair of black Timberland boots, lay on the bedroom floor, unopened.

Separated by bars, freedom lost

It is the most unlikely love story.

When the world labeled her fiancé guilty of a monstrous crime, Jewel refused to believe it. When the judge sentenced him to four decades in the Illinois penitentiary system, she stood by him.

"I love him," she would say. "It's as simple as that. He was good to me and my girls. He's a good man."

Ask a defense attorney how many clients profess innocence. Ask a prison warden how many inmates claim they are not guilty. The answer is the same: Denial is epidemic behind bars.

"We get about 200 to 300 new letters a month" from prisoners who say they've been wrongly convicted, says one attorney at the Innocence Project, a national nonprofit that works to exonerate the innocent. Since its inception in 1992, the group has used DNA testing to overturn convictions of 244 inmates.

By the time those prisoners won their freedom -- they had served an average of 12 years -- many had lost the bonds that would help them make a new life on the outside. One study shows marriages are three times more likely to fail when a man is incarcerated.

There is no movie night or anniversary dinner when a boyfriend or husband is locked up. Even for women like Jewel, single-minded about their loved one's innocence, time tests the relationship. Women face emotional abandonment and the challenges of a long-distance relationship. Sometimes financial responsibilities, the burden of single parenting and prejudice from outsiders drive them away.

If Jewel stuck by Dean, she'd be the rare exception.

Who would blame her if she simply moved on?

A smile that lit up the room

They met on an icy evening in Chicago in the winter of 1992. A crumpled scarf protected Jewel's face from the sharp wind as she walked home from her job as a waitress at the historic Daley's Restaurant. At her mother's house, where 23-year-old Jewel still lived, she found a stranger playing a video game with her cousin.

Dean Cage was 25, a thin man who flaunted his muscular 6-foot frame. He wore his hair trimmed short, curved along his head like M.C. Hammer. And he flashed a wide, animated smile.

"It lit up the room," Jewel remembers.

The two sipped Pepsi in the dining room and discovered shared passions: Both were raised Baptist and loved card games and children. Dean had three sons in Arkansas from a previous relationship; Jewel had two daughters. Neither Dean nor Jewel had ever married.

I love him. It's as simple as that. He was good to me and my girls. He's a good man.

--Jewel Mitchell

He worked at a warehouse that packaged paper cups. His manners were impeccable. Raised by his grandparents in Hope, Arkansas, he was a Southern gentleman who uttered "please" and "thank you" frequently.

That made her glow.

"He said he would come back the next day, but I didn't think it would be so soon," Jewel recalls. "He came back the next, and then the next day and then every day."

The two became inseparable. They went bowling together, barbequed hot dogs and chicken with cousins on the lakefront. They drank champagne at birthday parties, and giggled and danced until her heels were sore. After six months, they moved into a house with her daughters and became a family.

Jewel's mother adored her daughter's new boyfriend. An old-fashioned, churchgoing woman who believed in the sanctity of marriage, Jewel's mother, also named Jewel, married once and had nine children. She bombarded the couple with questions: When will you two get married? she teased.

After two years of dating, the proposal sprang casually from a conversation about children one day in September 1994.

I won't have another child out of wedlock, Jewel told Dean.

No silly, we're going to get married, of course, he responded. Will you marry me?

He already knew the answer.

The man in the funny hat

They set their wedding for the following spring: May 13, her mother's birthday. The couple looked at rings, and Jewel dreamed of green bridesmaid dresses.

But the wedding day passed with Dean in jail.

He sought a bench trial - putting his future in the hands of a judge - because his lawyer felt the heinousness of the crime and the victim's young age might make the jury biased.

In October 1996, the girl, by then 17, took the stand at a Cook County courthouse and told her story: A black man wearing a black leather motorcycle jacket and "funny looking hat" jumped her from behind at the corner of Wabash and 70th Street, threatened to kill her and dragged her into the basement of a building. There he sodomized, beat and performed oral sex on her.

A few days after the attack, police received an anonymous tip: The composite sketch made from the victim's description of her assailant resembled a man at a butcher shop. Police took the victim there and she identified Dean. She later testified that his voice sounded similar to her attacker's.

Dean testified in his own defense. He said he'd slept late on November 14, 1994, and didn't leave the house until 7:30 a.m., more than an hour after the incident occurred.

Jewel's testimony buttressed his. She said she and Dean were in bed together late that morning. But prosecutors grilled her about her black leather jacket, which they believed was the same leather motorcycle jacket worn by the assailant.

Dean's attorney argued there was no physical evidence to link his client to the crime.

After Dean's conviction, Jewel and her daughters moved back in with her mother, no longer able to live in their own place without Dean's support. Jewel's mother baby-sat the girls while her daughter waitressed and managed the cash register at Daley's, sometimes until 2 or 3 a.m.

The 45-minute train ride home on the Red Line felt like eternity. Her walk through South Side streets notorious for violence was like sprinting through a two-mile war zone, deflecting hollers and threats as drunks shot dice in the streets.

The extra money she scraped together went to finding a place she and the girls could call their own, a three-bedroom apartment above a church. Robbers ransacked the place twice while she worked the late shift. Thankfully, her daughters were at their grandmother's house.

"A lot of things would have been different if Dean were around," Jewel says. "If they knew he had been living there, they wouldn't have come."

But Dean wasn't there - except in the only way he could be, through phone calls and letters.

Transferred to four different institutions -- one on the opposite side of the state, more than four hours away - Dean worked in the prison laundry rooms and cafeterias. He was a model inmate who the guards liked so much they sneaked him outside during lockdown to shoot hoops.

On birthdays and holidays, he mailed cards and money orders to his three boys in Arkansas and to Jewel's daughters. Latoni and Latoya may not have been his biological children, but he treated them as if they were-something that always surprised Jewel's family.

"Before dad went away, I just remember laughs and smiles," says Latoni Mitchell, now 21. "When he was gone, it was hard to get through -- not just for my mom, but on the whole family."

With her mother at work, Latoni stepped in to help parent her sister, two years younger. Both girls grieved their father's absence.

He had brought them strawberry ice cream when their skin itched with chicken pox. He had attended PTA meetings and chaperoned on field trips to the Lincoln Park Zoo. Some kids envied the little girls whose father, unlike their own, visited the school so often.

Now the students taunted Latoni and Latoya, calling their daddy a rapist.

Connected by visits and letters

Nighttime was the most difficult. Dean sandwiched Jewel's perfume-scented letters into his pillowcase. Jewel wore his flannel pajamas to bed, trying to draw him close.

Despite their faith in God, they sometimes felt lost.

Why us, they asked. We are good people. Why does this happen to good people?

"It was almost like he was dead," Jewel says. "That's how bad it hurt."

Prison visits became a routine part of family life, and the trips were no vacation. The length of each visit hinged on the kindness of the guards. The frequency depended on how much money Jewel could save for gas.

"She was trying to live her life but never forgetting," says Audrey Vandurhust, Jewel's older sister, who served as the family photographer and sent shoeboxes full of family photos to Dean.

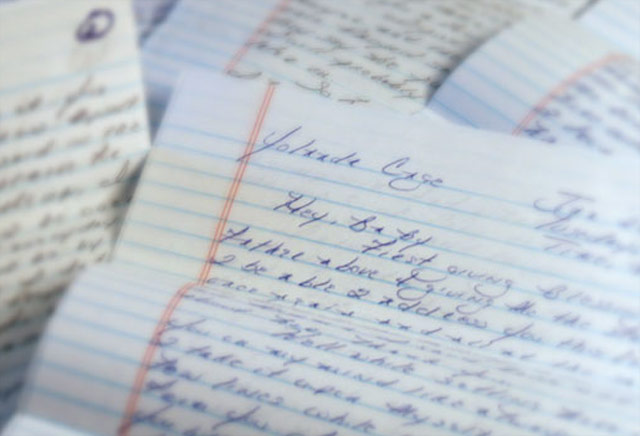

In between visits, the couple wrote.

Jewel's colorful cards captured her emotions. "When things get rough," one said, "I can feel God's kindness in your friendship, and I can feel his love lift me up when you reach out to me."

Dean peppered Jewel with questions about everyday life: "Have you heard anything else about your Section 8? How is your car running? Baby, I know you know you got to check on your oil and brakes every once in a while, right?"

He signed every letter the same way:

"Your one and only, Dean"

The legend of the Innocence Project

Two words are legend in the Illinois penitentiary system: Innocence Project. The story of one man's freedom becomes another man's hope.

Shortly after the judge found Dean guilty, an inmate at the Cook County Jail told him about the Innocence Project. Thus began a research project that would consume him behind bars - and, he hoped, set him free.

"It was a nightmare," Dean said. "Guys look at you funny when you're labeled a rapist. I had to keep defying the lies."

In the prison library, Dean dedicated hundreds of hours to scrutinizing his case and examining the law. What went wrong, what could have been done better? In December 1997, he filed his first appeal to the First District Appellate Court - and wrote his first letter to the Innocence Project

In both, Dean focused on tests for sexually transmitted diseases that both he and the victim underwent. He tested negative for chlamydia and trichomoniasis; the victim tested positive. The judge threw out the tests, arguing the results were irrelevant. They were never introduced at trial.

Guys look at you funny when you're labeled a rapist. I had to keep defying the lies.

--Dean Cage

Dean also raised questions about how he was identified. He pointed out that he had no prior record, and that there was no physical evidence linking him to the crime.

At the Innocence Project's New York office, Dean's letter did not go unnoticed. The attorneys wrote him back. They could not take his case - yet. But they would put it on a waiting list to be reviewed.

The nonprofit has limited resources to handle the thousands of letters they receive from inmates each year. It accepts only cases in which DNA testing can yield conclusive proof of innocence.

Wrongful convictions, the group found, occur in a number of ways: faulty witness identification, false confessions, police misconduct and poor legal representation. Witness misidentifications are responsible for three-fourths of wrongful convictions. And of those, about 70 percent of the inmates are minorities like Dean.

He was determined to leave the place he called a "hellhole."

In letters and visits, Dean told Jewel about the group that could fix this terrible mistake. By August 1998, they'd already used DNA to exonerate 11 inmates in the Illinois prison system.

Jewel dared to feel hope that Dean would be next.

A new proposal

Jewel was exhausted as she pulled into Danville Correctional Facility in central Illinois, a three-hour drive from her home in Chicago. Since Dean's arrest seven years earlier, she was working late to support her family and slept unusual hours. Her girls, now 13 and 11, could push her buttons, and she was tired on this particular day from dealing with their rebellion.

It was the summer of 2001, and Dean was still on the Innocence Project's waiting list - three years after he'd first written them. The courts had rejected his first appeal; the second, filed in 1999, awaited a response from the state of Illinois.

Sitting down across from Dean in the visitors' room, Jewel thought he looked weak and hunched over. The toll prison took on him sometimes came through the phone. He would call crying after witnessing a stabbing or a rape. Or tell her about cellmates who had killed family members and showed no remorse.

Dean had lost weight from the strain. So had Jewel. He knew, too, the unseen impact of his incarceration on Jewel.

He knew people in the community gossiped about her, called her crazy.

A childhood friend treated Jewel like an irrational teen. How do you even know Dean will want you when he gets out? she asked.

Friends offered to set her up on blind dates. Potential suitors flirted with her.

When Mitchell politely rejected the matchmaking offers, rumors swirled that she might be a lesbian. Even her older brother nudged her casually to reconsider: "Dean might be innocent" he said, "but it don't look good."

Dean didn't want Jewel to suffer any longer - or to remember him this way. He wanted something better for the fiancé he called "Baby." He swallowed his selfishness and made a very different proposal from the one he'd made on the day he asked her to marry him.

Move on, he told her.

Her cheeks grew warm, her heart raced.

What was he saying? Why would he tell her this? Had he found someone else?

It wasn't fair. She'd waited patiently for him.

Seven whole years.

Now what? Would she finally have to let go?

TOMORROW: The conclusion