Steve Dii

JF-Expert Member

- Jun 25, 2007

- 6,402

- 1,254

I find this to be the most exciting news for those into physics and the science of nature of particles. Pundit na wenzake must be jovial about this. I have been following news about this for a while. Sasa hivi countdown imeanza kutafuta "hapo mwanzo palikuwa na nini." The enigmatic nature of dark matter, alpha particles, et al is likely to be revealed in a couple of years. The machine will be commissioned on 10th Sept.

Zamani nilikuwa nawaza kama naruhusiwa kwenda popote pale - basi ningelienda kwenye space station. Leo hii nikijiuliza, jibu ni kwenda kuona hiyo Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the greatest scientific endeavor, the most complex scientific machine, the largest scientific equipment ever built....Please someni yafuatayo:

Cancel your plans for next Wednesday, it could be your last day on Earth. Or could it?

(Large Hadron Collider will not turn world to goo, promise scientists) Those in fear of what might become of this planet someni hapa: http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article4682260.ece

Blog ya wanaofatilia mambo mbalimbali kwenye LHC hii hapa: http://uslhc.us/blogs/?m=200809

SteveD.

Zamani nilikuwa nawaza kama naruhusiwa kwenda popote pale - basi ningelienda kwenye space station. Leo hii nikijiuliza, jibu ni kwenda kuona hiyo Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the greatest scientific endeavor, the most complex scientific machine, the largest scientific equipment ever built....Please someni yafuatayo:

The LHC is the world's most powerful particle accelerator, producing beams seven times more energetic than any previous machine, and around 30 times more intense when it reaches design performance, probably by 2010. Housed in a 27-kilometre tunnel, it relies on technologies that would not have been possible 30 years ago. The LHC is, in a sense, its own prototype.

Starting up such a machine is not as simple as flipping a switch.

Commissioning is a long process that starts with the cooling down of each of the machine's eight sectors. This is followed by the electrical testing of the 1600 superconducting magnets and their individual powering to nominal operating current. These steps are followed by the powering together of all the circuits of each sector, and then of the eight independent sectors in unison in order to operate as a single machine.

By the end of July, this work was approaching completion, with all eight sectors at their operating temperature of 1.9 degrees above absolute zero (-271°C). The next phase in the process is synchronization of the LHC with the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) accelerator, which forms the last link in the LHC's injector chain. Timing between the two machines has to be accurate to within a fraction of a nanosecond.

A first synchronization test is scheduled for the weekend of 9 August, for the clockwise-circulating LHC beam, with the second to follow over the coming weeks. Tests will continue into September to ensure that the entire machine is ready to accelerate and collide beams at an energy of 5 TeV per beam, the target energy for 2008. Force majeure notwithstanding, the LHC will see its first circulating beam on 10 September at the injection energy of 450 GeV (0.45 TeV).

Once stable circulating beams have been established, they will be brought into collision, and the final step will be to commission the LHC's acceleration system to boost the energy to 5 TeV, taking particle physics research to a new frontier.

‘We're finishing a marathon with a sprint,' said LHC project leader Lyn Evans. ‘It's been a long haul, and we're all eager to get the LHC research programme underway.'

CERN will be issuing regular status updates between now and first collisions. Journalists wishing to attend CERN for the first beam on 10 September must be accredited with the CERN press office. Since capacity is limited, priority will be given to news media. The event will be webcast through http://webcast.cern.ch, and distributed through the Eurovision network. Live stand up and playout facilities will also be available.

A media centre will be established at the main CERN site, with access to the control centres for the accelerator and experiments limited and allocated on a first come first served basis. This includes camera positions at the CERN Control Centre, from where the LHC is run. Only television media will be able to access the CERN Control Centre. No underground access will be possible.

Source: http://press.web.cern.ch/press/PressReleases/Releases2008/PR06.08E.html

Underground search for 'God particle'

By Paul Rincon

BBC News science reporter in Geneva, Switzerland

At the foot of the Jura Mountains, where Switzerland meets France, is a laboratory so vast it boggles the mind.

But take a drive past the open fields, traditional chalets and petite new apartment blocks and you will look for it in vain.

To find this enormous complex, you have to travel beneath the surface.

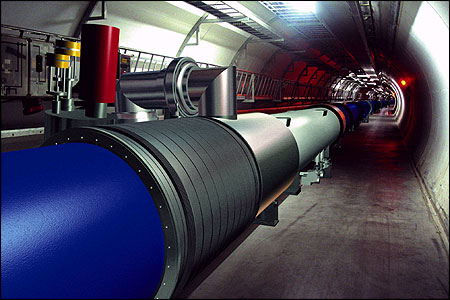

One hundred metres below Geneva's western suburbs is a dimly lit tunnel that runs in a circle for 27km (17 miles).

A circular tunnel runs for 27km under the French-Swiss border (pic: bbc)

Nature is much smarter than us. It might come up with a real surprise and that would be much more interesting - much more satisfying

Professor Jim Virdee, Imperial College London

The tunnel belongs to Cern, the European Centre for Nuclear Research. Though currently empty, over the next two years an enormous experiment will be installed here.

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is a powerful and impossibly complicated machine that will smash particles together at super-fast speeds in a bid to unlock the secrets of the Universe.

'New physics'

By recreating the searing-hot conditions fractions of a second after the Big Bang, scientists hope to see new physics, discover the sought-after "God particle", uncover new dimensions and even generate mini-black holes.

When completed, two parallel tubes will carry high-energy particles called protons in opposite directions around the tunnel at close to the speed of light.

The tunnel's huge circumference provides only the slightest of bends. Nevertheless, around 5,000 superconducting magnets are needed to steer and focus the particles around the tubes.

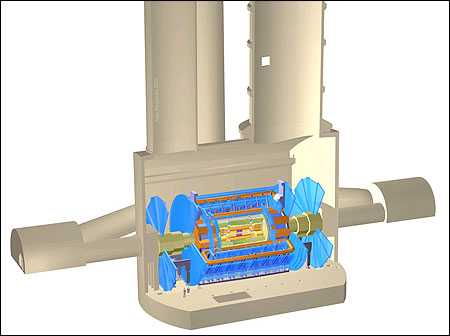

The Atlas experiment will join the search for the Higgs boson at Cern (pic: bbc)

"When the coils are energised there is one jumbo jet - 500 tonnes - per metre pushing outwards," says LHC project leader Lyn Evans.

Along the way, the proton beams will pass through enormous experimental instruments called detectors where they will cross.

When some of these protons collide at high energy, heavier particles can appear amongst the debris.

Great quest

When the LHC is turned on in the latter half of 2007, physicists will scour this crash wreckage for signs of the Higgs boson.

The Higgs is nicknamed the God particle because of its importance to the Standard Model, the theory devised to explain how sub-atomic particles interact with each other.

The 16 particles that make up this model (12 matter particles and 4 force carrier particles) would have no mass if considered alone. So another particle - the Higgs boson - is postulated to exist to account for this omission.

"The Standard Model is the best thing we've come up with so far," says Jim Virdee, spokesman for the team working on the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector.

But everyone recognises it is merely a stage on the way to something else. The Standard Model describes ordinary matter and yet astronomical observations show this makes up but a small part of the total Universe.

Needless to say, new theories are gaining ground and discoveries at the LHC could lead physicists towards a unified theory to explain how the Universe works.

"We are at a stage where the theorists do not know which direction to go in. The results from [our] experiment will determine which direction science takes," says Professor Virdee, who is based at Imperial College London, UK.

"We don't always like theorists to tell us what we should find. Nature is much smarter than us.

"It might come up with a real surprise and that would be much more interesting - much more satisfying."

Huge scale

The detectors at the LHC will count, trace and analyse the particles that emerge from the collisions between protons.

To call them experiments simply does not give an idea of their scale. The equipment weighs tens of thousands of tonnes and in some cases is as tall as a multi-storey building.

This week marked the inauguration of the enormous cavern at Cessy in France that will house the CMS. A 78m-long shaft leads up to the surface, through which the CMS will be lowered by crane early next year.

Both the CMS and its rival experiment, Atlas, are based on a cylindrical "onion" structure with several layers to perform different roles.

By 2010, nearly one billion collisions will take place every second in these detectors.

"CMS needs to collect a sample of several hundred collisions out of 40 million. And we have just three microseconds to decide whether a collision produced something interesting," Professor Virdee told the BBC News website.

High energy

After attending the CMS inauguration, we travelled just across the border to Switzerland, where the Atlas cavern is located.

Measuring 53m long, 30m wide and 35m high, it is taller than Canterbury Cathedral and is currently empty but for the support structures that will hold the detector in place.

"You're visiting at a good time; it won't look like this again," says Atlas technical co-ordinator Mark Hatch.

High radiation levels when the LHC is running mean access to these caverns will be forbidden when the machine is in operation, creating problems for the scientists.

The energies achieved by the experiment are 70 times greater than those of the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP) which previously occupied the tunnels at Cern.

Only by raising the bar will scientists be able to expand our current understanding of the Universe.

Whatever the discoveries ahead for physicists working at the LHC, the experiments will, according to its chief scientific officer, Jos Engelen, "keep physicists off street corners for a long time to come".

Story from BBC NEWS:

Cancel your plans for next Wednesday, it could be your last day on Earth. Or could it?

(Large Hadron Collider will not turn world to goo, promise scientists) Those in fear of what might become of this planet someni hapa: http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/article4682260.ece

Blog ya wanaofatilia mambo mbalimbali kwenye LHC hii hapa: http://uslhc.us/blogs/?m=200809

SteveD.