Geza Ulole

JF-Expert Member

- Oct 31, 2009

- 59,062

- 79,089

South Sudan: Keeping the Oil Flowing

Read about South Sudan’s emerging oil sector and more in the Africa Energy Series Special Report: South Sudan 2020 – the leading investor resource for tracking South Sudan’s current and future movements within the sector. Download the extended report and other AES Special Reports here.

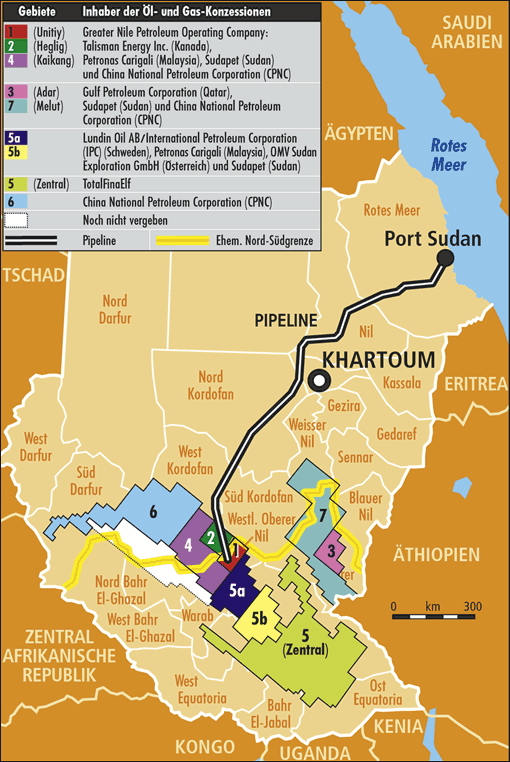

South Sudan exports its crude oil via pipeline from Hegleig and Paloch to Khartoum and then to Port Sudan. To keep the oil flowing, it has invited international companies to participate in investment opportunities in its refining and infrastructure sectors.

South Sudan’s economic lifeblood is intertwined with that of Sudan. Both nations are oil-dependent, but South Sudan maintains the bulk of the region’s 3.5 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, while Sudan owns the export pipelines, the refineries and sea access. One is useless without the other. Based on that interdependency, the two nations signed an agreement in 2012 under which South Sudan would compensate Sudan for the loss of oil production revenue and for the destruction of pipeline infrastructure caused by the civil war.

The compensation was agreed to amount to USD $3 billion, to be paid as a fee per barrel of oil produced, while the reconstruction of the oil infrastructure is expected to cost up to $1.5 billion according to the South Sudanese Petroleum Ministry. Initially designed to last for three and a half years, the Transition Financial Arrangement was extended in 2016 to reflect the collapse in oil price and global demand. In December 2019, the document was once again extended for a three-year period, set to end by March 2022. It establishes that South Sudan should pay $26 for each barrel transported through the Greater Nile Pipeline (GNP), operated by Petrolines for Crude Oil Ltd., and $24.1 for each barrel that passes through the Petrodar Pipeline, operated by the Bashayer Pipeline Company.

These fees include the actual crude oil transport costs and a $15 per barrel fee that corresponds to the $3 billion South Sudan must compensate Sudan for. After 2022, if no further extensions are needed, the cost per barrel should come down to $9.1 and $11 for the GNP and Petrodar pipelines respectively, reflecting the conclusion of that payment. The agreement also states that South Sudan must supply as much as 28,000 barrels of crude oil per day to the Khartoum refinery.

Another Path

Despite improved relations, dependency on Sudan’s oil infrastructure remains a risk and South Sudanese leaders wish to have alternatives. Hence, the country joined one of Africa’s biggest infrastructure developments; the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor project (LAPSSET), which is a multi-billion-dollar project spearheaded by Kenya to create a transport corridor for oil and other commodities.

The oil pipeline alone is expected to cost up to $4 billion. While the project seemed to have stalled over the last few years, in January 2020, LAPSSET received its biggest support yet, when the African Union announced it was adopting the project as its own, stating it would even be extended to form a continent-wide corridor connecting to Kribi Port in Cameroon. The African Development Bank, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa and the African Union’s New Partnership for Africa’s Development are all involved in promoting its implementation.

It is, however, uncertain how long the project will take to materialize and no new target date has been given for its conclusion.

Currently, the COVID-19 outbreak has forced the suspension of the second stage of the land surveys in Kenya, meant to assess the compensations needed for the land used for the pipeline.

Engage with the country’s oil sector opportunities firsthand at South Sudan Oil & Power 2021 – the nation’s flagship energy conference that will dictate the future of investment and development in the country. Click here to register.

MY TAKE: If Total or CNOOC r to enter into any sort of agreement with South Sudan to invest, South Sudan is to join EACOP!

South Sudan: Keeping the Oil Flowing