Interview with Julius Nyerere

Notes on a conversation with Nyerere at State House, Dar-es-Salaam, on August 10, 1963, were made by Professor Gwendolen M. Carter of Smith College, USA

Both interviewer and interviewee are deceased. This is a cleaned-up and edited version of a transcript which Gail Gerhart acquired from Thomas Karis many years ago. It does not appear on the Karis-Carter microfilms, but may be in the hardcopy of the collection at Northwestern University library, in the Melville J. Herskovits Africana collection.

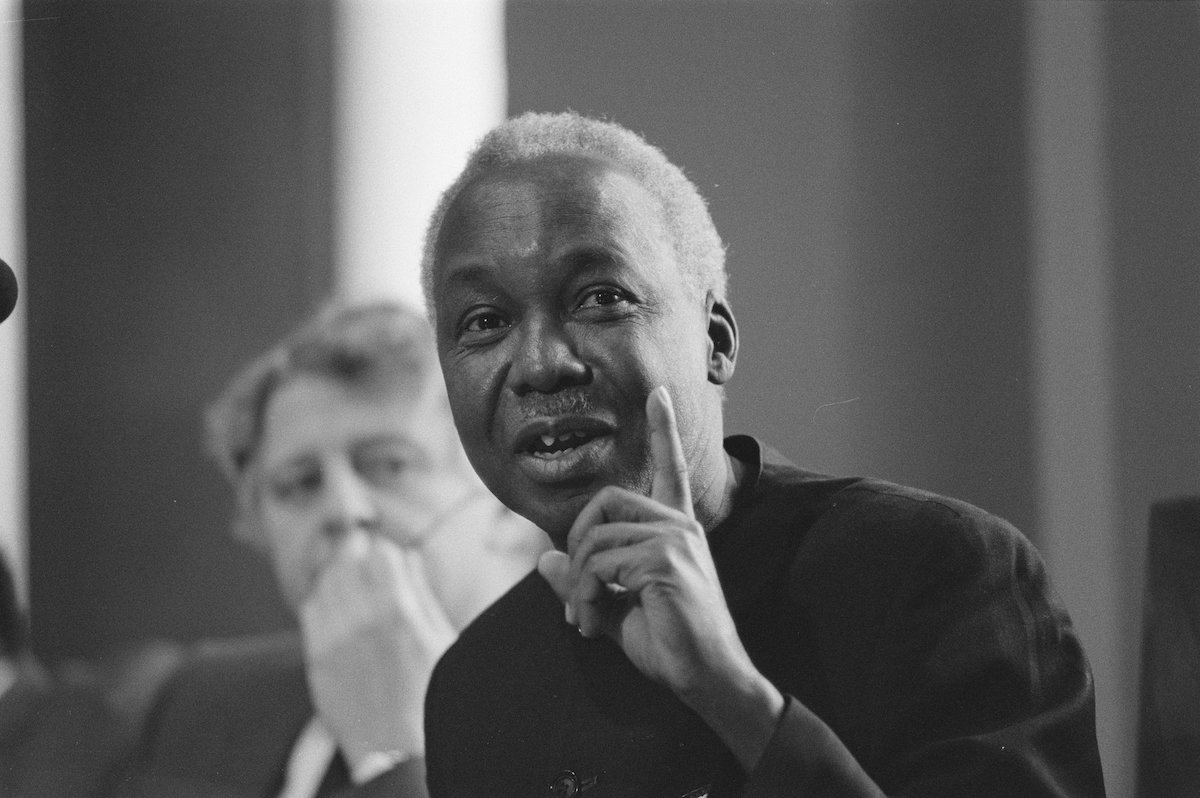

Julius Nyerere Julius K. Nyerere (1922-1999) was the first president of Tanzania (known as Tanganyika until 1964). He served as prime minister and then as president from independence in December 1961 until his retirement in 1985, except for a brief period shortly after independence when he stepped down temporarily to work on the revitalization of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU), the country's ruling party.

In May 1963 the Organization of African Unity was founded, and Tanzania became the headquarters of the Committee of Nine, an OAU body formed to coordinate assistance to liberation movements in African countries which had not yet achieved independence from colonial rule.

These notes on a conversation with Nyerere at State House, Dar-es-Salaam, on August 10, 1963, were made by Professor Gwendolen M. Carter of Smith College, USA. [Nyerere looks older and much more serious than I had remembered him. He still laughs frequently and whole-heartedly, but he assumes a very serious look the rest of the time. Presidential aide Joan Wicken took notes in shorthand. We sat on either side of his desk across from Nyerere who looks across the room to the gardens and the sea beyond. My last visit had been before independence in December 1961. Since then, Nyerere had temporarily resigned the presidency for a brief period to build up TANU separately from the state. He felt he had not succeeded in this and it was still a problem. He spoke of the inter-relationship of party and government and of the problem that former party leaders now were lost to the party because they were in government.]

I switched fairly quickly to the problem of South Africa. I put it in two terms: the problem of achieving change within South Africa itself and the problem of the division between the ANC and PAC.

He picked up the latter point first and said that he had put pressure on the two groups to form the common front. That was before Tanganyika's independence. Pressure had been put on the two in London also.

The common front was established for some time, but then it broke up.

He felt that the differences between the two groups were very considerable. He believed there was "a deep hatred" for each other. He felt there was less division over the alignment with communists maintained by the ANC than over tactics, that is that the PAC felt the demonstrations organized by the ANC were useless and the PAC felt more violent methods must be used.

He agreed that one of the values of the ANC was its experience and he stressed also the maturity of its leadership, although, at the same time, he felt that there were some leaders who were rather "slippery" and out for themselves. He also felt that the ANC could benefit from some of the PAC's fervor.

On the Committee of Nine, he said that all the money would henceforth be channeled through this group and thus the earlier danger of some African states backing the ANC and others backing the PAC would be avoided. In some situations, money would be given to that group, even if it was the only one there, which seemed best to serve the purposes of overthrowing the regime. In other instances, they hope to encourage a common activity. Perhaps they were coming closer to this.

He spoke of the recognition of [Holden] Roberto's group by Cyrille Adoula in the Congo as giving the Committee a surprise. The sub-committee of Six had gone to see the two rival Angolan groups, both of which had been represented in Dar at the time of the meeting of the Committee of Nine, and had endorsed Roberto also. He seemed a little surprised about his.

He did not speak about [Eduardo] Mondlane. On the question of approach, he felt that the Portuguese were not a serious problem. They were "weak." Also he was convinced—and he mentioned two soldiers who had spoken to him recently and whom he was sure were genuine—that the members of the Portuguese army did not trust each other, not knowing who was for the regime and who was against it.

He felt that the Portuguese territories were too dispersed and that the regime at home was too weak for serious resistance. He mentioned the fact of the Salazar speech that evening.

On Southern Rhodesia he felt that no action needed to be taken at this time. Joan had questioned me about the relative strength of [Ndabaningi] Sithole and [Joshua] Nkomo and it seemed fairly clear that the Tanganyikans back Sithole. Obviously, as we had been told elsewhere, Southern Rhodesia is not looked on as a difficult situation to solve.

South Africa, he declared, was a difficult problem in Africa. It would not be possible to move against South Africa forcefully until after Southern Rhodesia and the Portuguese territories had come under African control.

He agreed that there was a very intense feeling about South Africa and spoke of it as "a block to African unity."

On his discussions with [US President John] Kennedy, he was particularly interesting. He had gone to the United States particularly to discuss South Africa and the Portuguese territories. I did not ask him, and he did not mention, whether he went as the agent of the Committee of Nine or not. What he had in mind when he went was to tell Kennedy that if the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Germany united to tell South Africa that it must change its policy, he was convinced that the South Africans would.

He found Kennedy "radical" in his approach. Kennedy believes that apartheid is "a religion." He has had someone from Mississippi "quote the Bible" to him [regarding race].

Kennedy believes that only an "internal explosion" can change the situation. [Secretary of State Dean] Rusk is more legalistic than Kennedy and the latter seemed to feel that perhaps events in South Africa would be necessary in order to convince Rusk of the necessity of intervention.

Nyerere had become convinced about the advantage of an oil boycott in America itself where the idea was first broached to him. He is now busy selling it. Also he felt that South West Africa and the International Court decision might offer an opening for American action. He had not discussed this with Kennedy, but he felt that the American approach was a legalistic one and that it would be an advantage to have a legal decision on which to act.

When I asked him what he felt one should try to persuade the United States to do, he said, "push to the maximum of action that can be achieved." At the moment, the total arms boycott is the maximum, but perhaps there will be more that can be done.

Keep up the pressure as one sees what can be added. There is no use pressing for too much, e.g. expulsion from the United Nations or a total boycott. One must work for what is feasible, but keep up the pressure. I asked whether it would be better to lay off South Africa until after the Portuguese territories and Southern Rhodesia had been settled, but he did not think so. He reiterated that it was important to have the maximum amount of pressure exerted.