Rutashubanyuma

JF-Expert Member

- Sep 24, 2010

- 219,470

- 911,172

[h=1]Britain in grip of worst ever financial crisis, Bank of England governor fears[/h] £75bn more quantitative easing announced by Sir Mervyn King to boost demand in economy

- Larry Elliott and Katie Allen

- guardian.co.uk, Thursday 6 October 2011 20.35 BST Article history

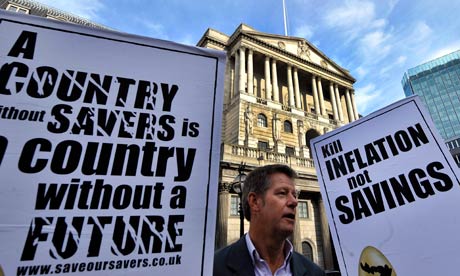

Sir Mervyn King said Britain was suffering from an 1930s-style shortage of money. Photograph: Chris Ratcliffe/PA

Sir Mervyn King expressed fears that Britain is in the grip of the world's worst ever financial crisis after the Bank of England announced it was injecting £75bn into the ailing economy.

The Bank's governor said the UK was suffering from a 1930s-style shortage of money and needed a second dose of quantitative easing to boost demand and prevent inflation falling too low.

Shares rose strongly in the City, posting a rise of almost 200 points, after Threadneedle Street responded to growing evidence of a looming double-dip recession and the deepening crisis in the eurozone with a four-month programme of electronic money creation. Dismissing concerns that the action risked adding to inflationary pressure, King said Britain was now facing a different problem from the days when too much money flowing round the economy pushed up the annual cost of living. "There is not enough money. That may seem unfamiliar to people." he told Sky News. "But that's because this is the most serious financial crisis at least since the 1930s, if not ever."

George Osborne agreed to King's request to be able to expand the asset purchase scheme under which the Bank buys government bonds from commercial banks. The chancellor said further steps would be taken to boost growth in his autumn statement next month.

"Given evidence of continued impairment in the flow of credit to some parts of the real economy, notably small and medium-sized businesses, the Treasury is exploring further policy options," Osborne said in a letter to the governor. "Such interventions should complement the monetary policy committee's [MPC] asset purchases."

Britain's first dose of quantitative easing, also known as QE1, was in 2009/10, with £200bn being injected into the economy. Labour said the launch of QE2 was an admission that the government's economic policy had failed.

Ed Balls, the shadow chancellor, said: "With our economy stagnated since last autumn David Cameron and George Osborne are now betting on a bailout from the Bank of England. The government's reckless policy of cutting spending and raising taxes too far and too fast is demonstrably not working. But rather than change course the government has spent the last week urging the Bank of England to step in and essentially print more money."

Some in the City were caught unawares by the scale and the timing of the Bank's move. Last month, only one of the nine members of the MPC, Adam Posen, voted for more QE, but the mood has changed in response to poor domestic news and concerns that Europe's sovereign debt crisis risks a repeat of the mayhem three years ago following the bankruptcy of the US investment bank Lehman Brothers.

"The pace of global expansion has slackened, especially in the United Kingdom's main export markets," the MPC said in a statement explaining its decision. "Vulnerabilities associated with the indebtedness of some euro-area sovereigns and banks have resulted in severe strains in bank funding markets and financial markets more generally. These tensions in the world economy threaten the UK recovery."

The MPC said the slowdown in the UK economy, which saw no growth in the nine months to mid-2011, had in part been caused by temporary factors, but added that there was also evidence that the underlying pace of activity had weakened. It said the squeeze on real incomes caused by inflation running well ahead of wage increases and the impact of Osborne's austerity programme were "likely to continue to weigh on domestic spending".

King admitted that inflation could breach 5% next month but said that would be the peak. Analysts said the Bank was now clearly more concerned about the risks of recession than about the possibility of a rise in inflation. Figures released by the Office for National Statistics this week showed that the downturn of 2008/09 was even deeper than originally believed, with gross domestic product dropping by 7.1% in the biggest recession since the second world war. The flatlining of the economy since last autumn has left activity still 4.4 percentage points below its 2008 peak.

The TUC's general secretary, Brendan Barber, said the decision to expand QE was the right one, but added: "While it is better than not doing anything, quantitative easing is no economic magic wand.

"We worry that it does more to help the finance sector than the rest of the economy and could fuel further inflation at a time when living standards are already being squeezed."

Business leaders welcomed the move. Graeme Leach, chief economist at the Institute of Directors, said: "Near-zero GDP and money supply growth made a compelling case and the Bank of England was right to launch QE2. It could be argued that the Bank of England was slow to introduce QE the first time, but thankfully it hasn't made the same mistake twice."

By the end of the four-month programme, the Bank will have bought a total of £275bn in assets from banks, around 20% of GDP. The news prompted alarm in Britain's pension funds, which are concerned that QE pushes down interest rates and reduces the return on their investments, but Threadneedle Street left the door ajar for a further expansion of QE2 should the economy not respond.

Michael Saunders, UK economist at Citi, said the deteriorating outlook for the economy would require the Bank to "do QE on a very big scale". He added: "We expect the cumulative total of QE (now heading to £275bn) will eventually reach £500bn or so. It may go even higher than that."